Hedge fund profits from ashes of foreclosure

Hedge fund profits from ashes of foreclosure

For Shanika Henderson the dream of owning her own home is on hold, but she can?t help wondering if her landlord took that dream away from her and hundreds of other potential home-owners in North Minneapolis.??

MINNEAPOLIS (FOX 9) - For Shanika Henderson the dream of owning her own home is on hold, but she can’t help wondering if her landlord took that dream away from her and hundreds of other potential home-owners in North Minneapolis.

"Some stories are heart-wrenching, what people have to endure just to have a home, it’s horrible," Henderson said.

She rents her house in the Folwell neighborhood on Girard Avenue North from a company called HavenBrook.

In the eight years she’s lived in the home she has watched it slowly fall apart.

On a recent afternoon, she gave a tour of the home’s leaking basement, water damage, sagging floors, and pointed out a stove that had been leaking gas.

And while HavenBrook promises 24-hour repairs, she said it rarely delivers.

"I guess you kind of have the good and the bad, but I went with the bad for a very long time," Henderson said.

Shanika Henderson, Havenbrook renter

In Minnesota, HavenBrook owns more than 600 single-family homes, but a third of its inventory – 199 homes– are in North Minneapolis.

Minneapolis city inspectors have received 273 complaints and documented 1,594 violations in HavenBrook homes since 2018. Among those violations, 103 involved ‘life safety and quality of life.’

In Columbia Heights, the city revoked the rental licenses for 21 HavenBrook homes because of the failure to resolve code violations in two rental homes.

Earlier this month, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison filed a first of its kind lawsuit against the company, saying HavenBrook deceived and defrauded their tenants.

Tenants are also organizing through a group called United Renters for Justice and have been demanding a meeting with HavenBrook.

THE AMERICAN DREAM vs. WALL STREET INVESTORS

But this isn’t just another bad landlord story.

HavenBrook and companies like it, who convert single-family homes into rental units, represent a fundamental shift in how to think about housing.

What was once considered a time-honored way for American families to build generational wealth, single-family housing is now a new investment class and mechanism for Wall Street to get richer.

Realtor Lisa Carter specializes in first-time buyers in North Minneapolis.

In a hot market, with multiple bids, her clients often get frozen out. In some cases, she believes her clients have lost out to investors paying with cash.

"That's one of my least favorite parts of my job is telling the client that they didn't get their home, it just makes me cringe," Carter said.

A RACIAL GAP, GETTING WIDER

There’s a lot to make people cringe about home buying these days.

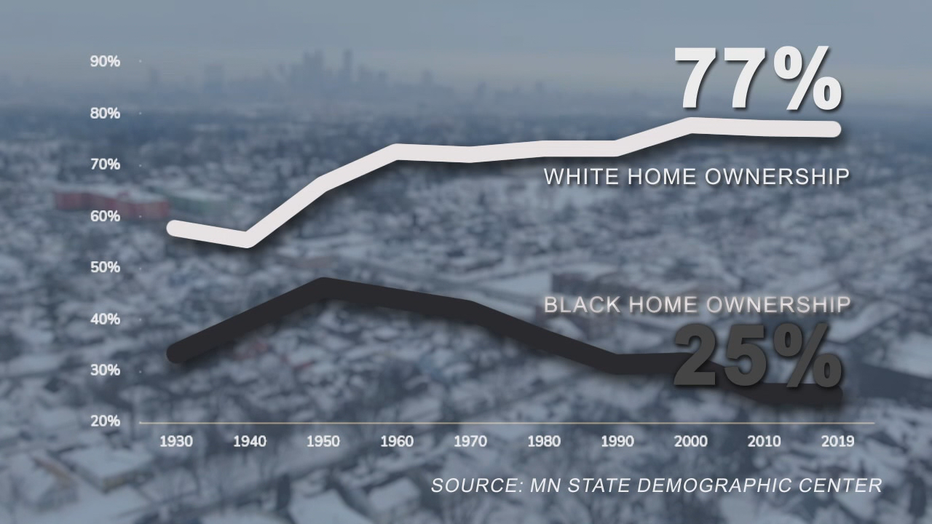

The Twin Cities region has one of largest racial gaps for homeownership in the nation, despite having very high levels of home ownership overall, according to the Minnesota State Demographic Center.

That racial gap is especially wide in Minneapolis where white home ownership is 77%, while Black home ownership is only 25%.

In Minneapolis, white home ownership is 77%, while Black home ownership is only 25%.

If owning a home is still part of the American dream, the opportunities are hardly the same.

A dashboard of data developed by the Minneapolis Federal Reserve shows the number of investor-owned single-family homes in the Twin Cities has doubled in the last 15 years, from 1.8% to 4%.

In North Minneapolis, HavenBrook and other out of town investors own as much 16% to 24% of the homes, in some of the poorest census tracts in the city.

Libby Starling, Director of Community Development and Engagement with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis said the Fed developed the dashboard to have real data instead of speculation about the impact of investor ownership of single-family homes.

"Where is the line between a business opportunity and a business model and something that makes us uncomfortable as a community? Starling said. "It's capitalism in action."

HavenBrook’s focus on North Minneapolis was no accident, it was a strategy, said Yonah Freemark, a researcher with the Urban Institute who examined "Who Owns the Twin Cities?" and found HavenBrook at the top of the list.

The study, which relied on regression analysis of single-family home ownership patterns, showed investor ownership is widening the racial gap in home ownership.

"I think their strategy was very clearly to target communities where foreclosure rates were highest, where homeowners were most vulnerable, and in the Twin Cities region North Minneapolis was the center of the foreclosure crisis, and they swooped up and took advantage of that," Freemark said.

FROM THE ASHES OF FORECLOSURE

To understand the rise of HavenBrook and companies like it, just go back to the foreclosure crisis in 2007, when predatory lenders decimated North Minneapolis, with not just risky sub-prime loans, but outright criminal fraud.

It left thousands of homes on the north side under water, empty, and boarded up. Where most people saw financial ruin, Wall Street glimpsed an opportunity.

HavenBrook, a private-equity fund based in Georgia, was one of several large investors including Blackstone, Apollo Capital, Invitation Homes, and Zillow that spent $36 billion gobbling up more than 200,000 homes nationwide.

HavenBrook and other companies did it with government-backed, interest-only loans from Freddie Mac.

"It seemed like a good idea to move homes from being vacant to having someone owning them as a rental opportunity. That seemed like a positive," Starling of the Fed said.

"The challenge is when that begins to get out of whack, and some of these owners aren't your neighbor down the street, but maybe the neighbor in the Virgin Islands," she said.

RETURN OF THE ‘BIG SHORT’

HavenBrook, the original buyer of the homes, is now just a shell company. It was bought in 2018 by Front Yard Residential, based in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Front Yard was bought last year by a New York hedge fund called Pretium Partners which already owned 70,000 rental homes around the country under the name Progress Residential.

Its founder and CEO is Don Mullen Jr., the guy behind the so-called ‘Big Short’ of the housing market.

Back in 2007, when he worked at Goldman Sachs, Mullen bet the housing bubble was about to burst and shorted the market by buying so-called ‘credit-default swaps.’ Now Mullen is betting those who lost their homes, will be forced to rent.

In a pitch to investors, uncovered as part of the Panama Papers, Mullen said the strategy is to "capitalize on the severe distress in the residential real estate market in the United States," renting homes to families "who have been displaced by foreclosure or are otherwise unable to obtain financing despite being able to afford a home purchase."

Freemark, the researcher behind ‘Who Owns the Twin Cities?’ said the strategy harms the very people who could benefit the most from home ownership.

"Frankly, it's harder to become a homeowner when there aren't enough homes available in the first place. And when the homes that are available are being sought out by large investors who can pay a higher cost to be able to buy them in the first place and then hold on to them for a longer period of time," Freemark said.

A BIG ‘EQUITY’ SUCK

To understand the real-world impact of the investment strategy, consider Shanika Henderson’s rental home.

HavenBrook bought the home on Girard Avenue North in 2014 for $59,000, today it is worth $141,500, a 140% increase. That is $82,500 in equity that could’ve gone to her four children, instead going to a hedge fund.

"It saddens me that I could have done something like that," Henderson commented.

Now, expand the frame. HavenBrook purchased the 199 homes in North Minneapolis for $18,321,341. Today they’re worth $30,112,000, a 64 percent increase. That is $11,790,659 in equity sucked out of neighborhoods that can least afford it. And it doesn’t even count the rent the company takes in.

Many HavenBrook homes operate as Section 8 public housing. Minneapolis Public Housing has paid Havenbrook $6,541,696 since 2018.

HavenBrook, a private-equity fund based in Georgia, was one of several large investors including Blackstone, Apollo Capital, Invitation Homes, and Zillow that spent $36 billion gobbling up more than 200,000 homes nationwide.

A HEDGE FUND RESPONDS

Pretium declined interview requests.

In statements to the FOX 9 Investigators from its public relations firm, Pretium distanced itself from the investment strategies of the companies it acquired in 2021, saying it "can’t comment on Front Yard’s local investment strategies."

Pretium said since acquiring Front Yard Residential last year its invested $65 million in renovations and maintenance nationwide.

"Under new ownership, we have quadrupled our local maintenance team and continue to invest significantly to support renovations and maintenance repairs for residents to address pre-existing conditions and enhance the resident experience," Pretium said in its statement.

A TAX ON ‘INVESTOR’ HOMES?

That will be news to their tenants as well as Minnesota’s Attorney General.

A bill at the Minnesota legislature, backed by the League of Minnesota Cities, would impose an additional sales tax on investors who convert owner occupied homes into rentals.

Yet, such a tax could be regressive because unless the percentage increases with the price of the home, it would offer less of a disincentive to convert lower priced homes in more marginalized communities.

For many in North Minneapolis the arrival of hedge fund investors in their neighborhoods is part of a larger pattern, as history and housing go hand in hand, from the legacy of housing covenants to redlining by banks.

In the 21st century it’s been predatory lending, followed by bottom feeding investors.

For those left out, like Shanika Henderson who lost a lifetime of security and $80,000 in equity by not owning her home, it feels like a hijacking of the American dream.

"I get it that they're a company, and they're meant to make money and put as little as possible into the homes that they’re renting," Henderson said. "But to me, it's more it's B.S, you know, you still need to take care the people that feed you and your family as well."