James Webb telescope finds massive galaxies dating back to beginning of universe

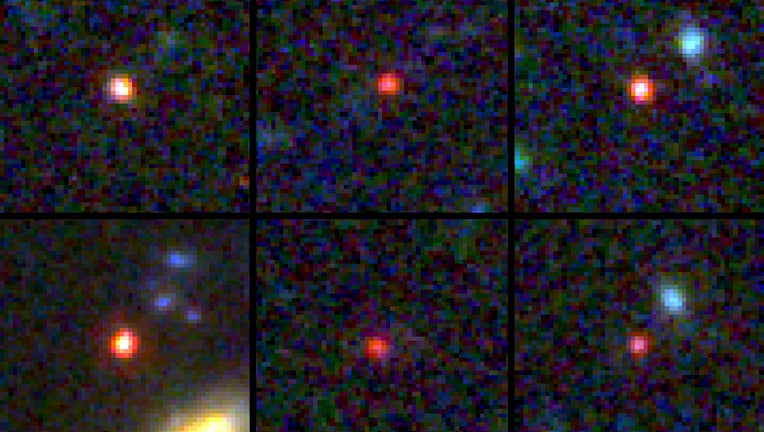

Images of six candidate massive galaxies, seen 500-800 million years after the Big Bang. One of the sources (bottom left) could contain as many stars as our present-day Milky Way, but is 30 times more compact. These images are a composite of separate (NASA, ESA, CSA, I. Labbe (Swinburne University of Technology). Image processing: G. Brammer (Niels Bohr Institute’s Cosmic Dawn Center at the University of Copenhagen)

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. - Astronomers have discovered what appear to be massive galaxies dating back to within 600 million years of the Big Bang, suggesting the early universe may have had a stellar fast-track that produced these "monsters."

While the new James Webb Space Telescope has spotted even older galaxies, dating to within a mere 300 million years of the beginning of the universe, it’s the size and maturity of these six apparent mega-galaxies that stun scientists. They reported their findings Wednesday.

Lead researcher Ivo Labbe of Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology and his team expected to find little baby galaxies this close to the dawn of the universe — not these whoppers.

"While most galaxies in this era are still small and only gradually growing larger over time," he said in an email, "there are a few monsters that fast-track to maturity. Why this is the case or how this would work is unknown."

Each of the six objects looks to weigh billions of times more than our sun. In one of them, the total weight of all its stars may be as much as 100 billion times greater than our sun, according to the scientists, who published their findings in the journal Nature.

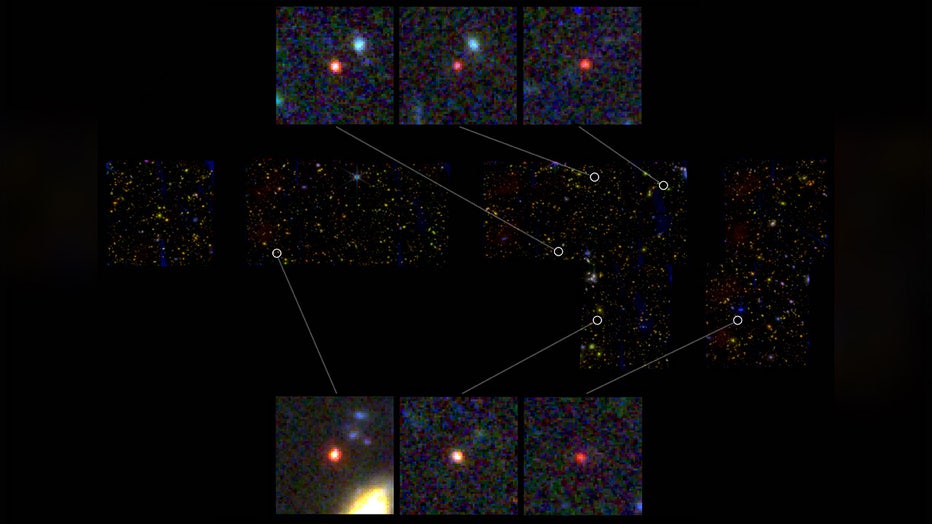

(NASA, ESA, CSA, I. Labbe (Swinburne University of Technology). Image processing: G. Brammer (Niels Bohr Institute’s Cosmic Dawn Center at the University of Copenhagen).)

Yet these galaxies are believed to be extremely compact, squeezing in as many stars as our own Milky Way, but in a relatively tiny slice of space, according to Labbe.

Labbe said he and his team didn’t think the results were real at first — that there couldn’t be galaxies as mature as the Milky Way so early in time — and they still need to be confirmed. The objects appeared so big and bright that some members of the team thought they had made a mistake.

"We were mind-blown, kind of incredulous," Labbe said.

The Pennsylvania State University’s Joel Leja, who took part in the study, calls them "universe breakers."

"The revelation that massive galaxy formation began extremely early in the history of the universe upends what many of us had thought was settled science," Leja said in a statement. "It turns out we found something so unexpected it actually creates problems for science. It calls the whole picture of early galaxy formation into question."

These galaxy observations were among the first data set that came from the $10 billion Webb telescope, launched just over a year ago. NASA and the European Space Agency’s Webb is considered the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, coming up on the 33rd anniversary of its launch.

Unlike Hubble, the bigger and more powerful Webb can peer through clouds of dust with its infrared vision and discover galaxies previously unseen. Scientists hope to eventually observe the first stars and galaxies formed following the creation of the universe 13.8 billion years ago.

The researchers still are awaiting official confirmation through sensitive spectroscopy, careful to call these candidate massive galaxies for now. Leja said it's possible that a few of the objects might not be galaxies, but obscured supermassive black holes.

While some may prove to be smaller, "odds are good at least some of them will turn out to be" galactic giants, Labbe said. "The next year will tell us."

One early lesson from Webb is "to let go of your expectations and be ready to be surprised," he said.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.