The universe is expanding more quickly than previously thought, scientists say

Universe will double in size in 10 billion years, faster than previously thought

"The funny thing is, it doesn’t match the prediction. Which is strange but exciting because in science, any time something doesn’t match your model, you have the potential to learn more about your model or your understanding," the study's lead author and Nobel Laureate, Adam Riess, said.

The universe is expanding more quickly than previously believed, and scientists aren’t really sure why.

A recent study, which is set to be published in the Special Focus issue of The Astrophysical Journal, said that new results more than double the prior sample of cosmic distance markers used to measure the expansion of the universe.

Nobel Laureate Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and his team, along with the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, "reanalyzed all of the prior data, with the whole dataset now including over 1,000 Hubble orbits."

Hubble orbits mean the number of times the Hubble Space Telescope orbits the Earth, which is what was used to collect over 20 years’ worth of data to result in these recent findings.

"You are getting the most precise measurement of the expansion rate for the universe from the gold standard of telescopes and cosmic mile markers," Riess said.

When comparing measurements from previous data and the current data, Riess’ team found that the rate at which the universe is expanding was off.

Previous measurements predicted the universe was expanding at a rate of 67.5 plus or minus 0.5 kilometers per second per megaparsec, according to NASA. However, Riess’ team showed the universe is actually expanding 73 plus or minus 1 kilometer per second per megaparsec, which predicts the size of the universe will double in about 10 billion years.

"The funny thing is, it doesn’t match the prediction. Which is strange but exciting because in science, any time something doesn’t match your model, you have the potential to learn more about your model or your understanding," Riess told FOX TV Stations.

"So we’re at a point now where it’s not just bad luck that these don’t match each other. We’ve done too many measurements and cross-checked them too much to say it’s bad luck. So now we have to really put our thinking caps on and understand why is it that you can’t go from the beginning of the universe to the end with a story that connects the two and something breaks down along the way," Riess added.

How is the expansion of the universe measured?

Scientists measure the expansion of the universe using the Hubble constant (Ho).

When tracking the growth of a child, one might mark a door frame indicating the child’s height, date and time. The same would go for measuring how fast the universe expands. Scientists use cosmic mile markers such as distant galaxies and stars to track how far and how fast the universe has expanded.

"We have to measure how tall, which in this case means how far away things are, and the time stamp which is like measuring something else we call the red shift, and it’s basically how far away, how fast things are expanding away from us. And so in our case, the hard part is measuring how far away things are, and we use the Hubble Space Telescope to look at stars very, very far away and if we can recognize what kind of stars they are, then we can know how luminous they ought to be and then comparing that to how faint they actually are tells us how far away they are," Riess explained.

The most recent measurement is accurate with a 1 1/2% uncertainty, which, according to Riess, is very accurate.

In this most recent study, the universe is believed to be expanding at a Hubble constant value of 73 plus or minus 1 kilometer per second per megaparsec.

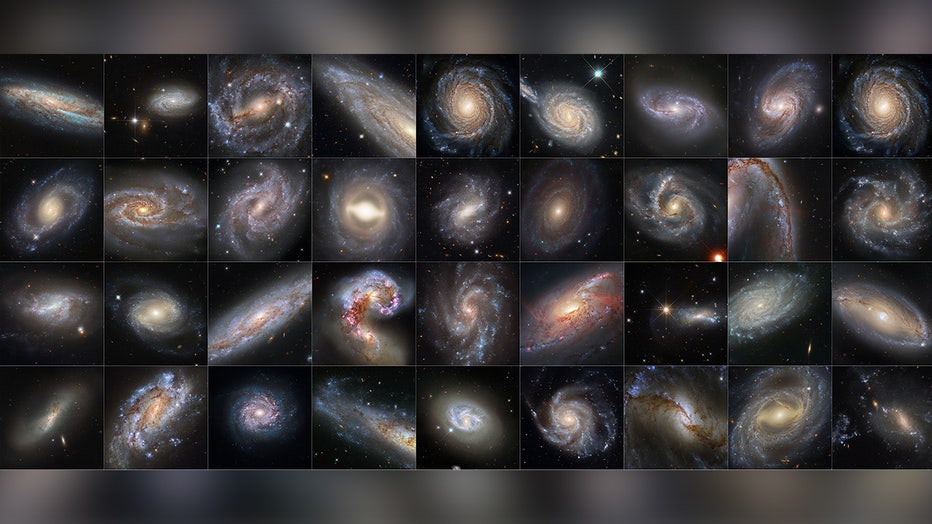

This collection of 36 images from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope features galaxies that are all hosts to both Cepheid variables and supernovae. These two celestial phenomena are both crucial tools used by astronomers to determine astronomical distance (NASA, ESA, Adam G. Riess (STScI, JHU))

A new kind of physics

This newest discrepancy isn’t exactly bad news, according to Riess. In fact, it opens up a whole new avenue of possibilities to further our knowledge of what’s going on in that big expansion of darkness dotted with galaxies.

The current hypothesis as to why the numbers aren’t matching up for how quickly the universe is expanding could be because there is a new kind of physics of which scientists are unaware.

Some examples of newer physics that were discovered in recent years include dark matter and dark energy.

So far, 96% of the universe is made up of dark and unknown parts, according to Riess. Dark matter makes up about 30% of that and dark energy makes up between 65%-70%.

While Riess said it isn’t exactly certain what this new physics could be and, because this is just a hypothesis, more research needs to be done and that’s always exciting.

"I tend to find that there’s almost two kinds of people, those who are completely fascinated about the mystery of what’s out there; where do we come from; what’s the universe made of; how did it start, how old is it; what’s going to happen; where do we fit in all this? And to those people, they understand immediately, ‘Wow, this is really profound.’ And then, I’ll admit, there are people who are like, ‘Wow, why would I ever care, why even look up? Everything’s down here.’ And it’s not true that everything’s down here. Mostly, everything’s up there, but I understand that what those people care about is happening here on planet Earth. And to those I would just say, we’re curious. I would also say, that we want to understand the laws of physics better," Riess said.

And, if it happens that a new type of physics is discovered, Riess predicts this will inspire more technological advancements and essentially create a snowball effect of innovation.

What will future research include?

While the Hubble telescope is predicted to last another two decades, Riess said that the newer James Webb Space Telescope has the potential to pick up from where the Hubble will leave off and scientists can continue to figure out exactly what’s going on in our expanding universe.

This story was reported out of Los Angeles.