Why the Northern Lights this week were a bust: Curbing misinformation

The aurora borealis could be seen on the North horizon in the night sky over Wolf Lake in the Cloquet State Forest in Minnesota around midnight on Saturday morning. The KP index was high in the early morning hours of Saturday September 28, 2019 which (Getty Images)

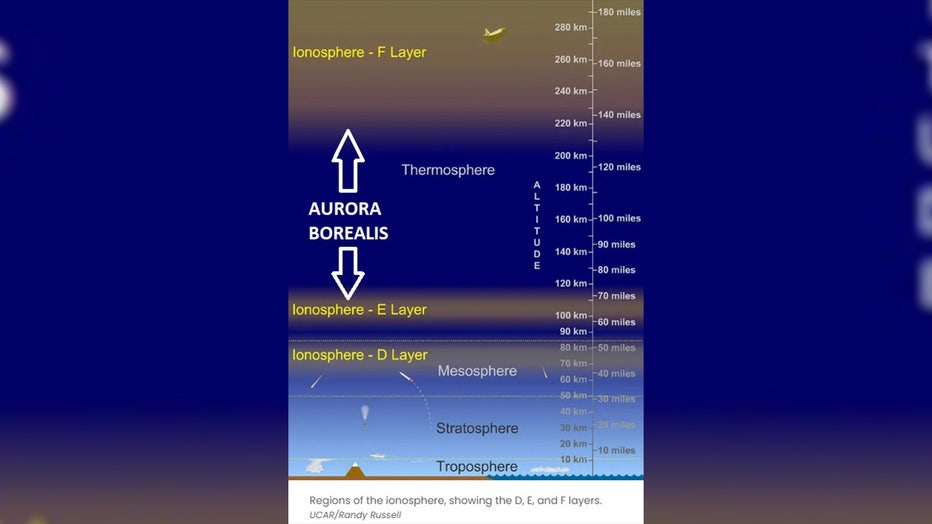

MINNEAPOLIS (FOX 9) - The Aurora Borealis has long been known as one of the most spectacular sights on the planet, but it's also one of the most elusive. Despite what it may look like, the Northern (and Southern) Lights are NOT weather. While they do technically occur in our atmosphere, they occur dozens of miles above the highest cloud tops. The light show is the effect seen as our atmosphere (and more specifically our ionosphere) reflect, refract, and block a majority of harmful particles moving through space courtesy of our sun. The ionosphere is generally part of our Thermosphere, or the outer layer of our atmosphere.

As seen in the above image, the aurora most often occur in what's called the "E" layer of the ionosphere, which is located roughly 60 to 70 miles above the Earth's surface. However, for the most brilliant of shows, the aurora can be 100 or more miles tall and can include a lot of the "F" layer as well. This happens when a large amount of the sun's "debris" reacts with our atmosphere. Yes, our sun creates "debris". If it weren't for our atmosphere or our "shield" around the Earth, it would be uninhabitable. But because it's NOT weather and the source of these particles are roughly 94 million miles away; the prediction of this phenomenon is difficult, to say the least.

Over this past weekend, a story made the rounds that was predicting "widespread" and "brilliant" Northern Lights several days away for much of Canada and the northern U.S. Where this story came from and ultimately why it made the rounds on social media and reputable sites alike, I really have no clue. It may have been a legitimate source or not, but nevertheless, it got traction and spread. But when I learned of this on Monday (I checked out over the weekend because I was out of town) my immediate thought was we'd all been duped.

Be skeptical of long-range Aurora forecasts

Epic wedding photo during Northern Lights

Wedding photos are memorable keepsakes, and one local wedding photographer caught an epic one with assistance from Mother Nature on the shores of Lake Superior.

In my opinion, you should be VERY skeptical of an aurora forecast of any kind, especially when that forecast discusses a period more than 36 hours away. This is because the specifics of how coronal mass ejections (CME) or solar storms work is a relatively new science.

New satellites and instrumentation have made our understanding and prediction of the aurora far more accurate over the last couple of decades, but there's still a lot of unknowns. Think of forecasting the aurora like what forecasting the weather was like in the 1970s. Technology and our understanding was rapidly increasing, but even a 24-hour forecast wasn't all that accurate. Now a continued increase in research and technology is allowing that forecast to improve quickly, but I still believe we're still many years away from making these accurate enough to depend on, especially since local conditions (what you see out your window) can vary drastically over short distances.

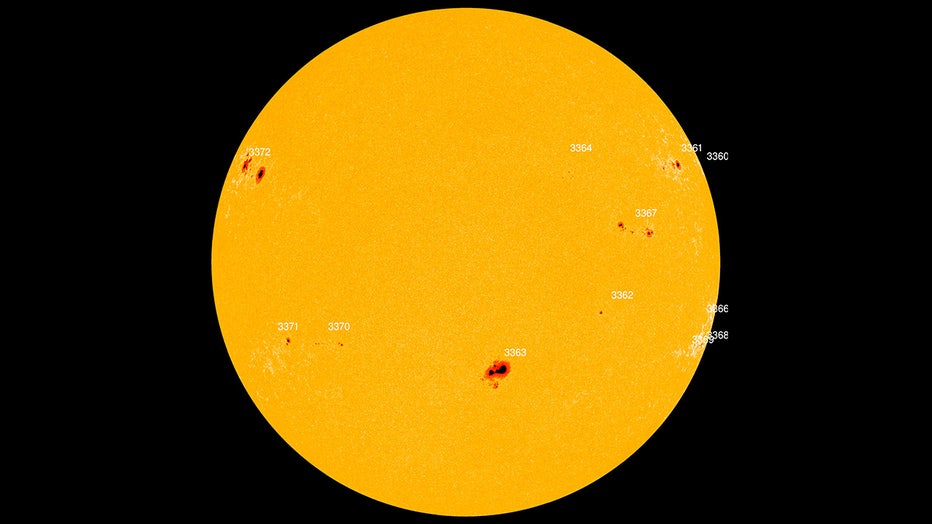

Current sunspots and their corresponding number on the Earth facing side of the sun. (Courtesy of spaceweather.com)

The Northern Lights are Earth's response to blocking harmful particles from the sun. These harmful particles are omnipresent because obviously, the sun is always there, sending radiation (warmth) toward the planet. But occasionally the sun will send a sudden wave of particles called a coronal mass ejection (CME) out into the solar system. These CMEs originate from sunspots or seemingly small darker spots located around different sections of the sun. These sunspots are actually cooler pockets on the sun that are less "stable" and are unable to prevent the sun from losing some of its plasma and other particles located on the surface. So occasionally, these particles get launched off the surface and into space in whatever direction they are facing. Sometimes they head toward Earth, sometimes not — that's one of the many reasons why predicting them is difficult.

But the Northern Lights may be more active and include more of the U.S. over the next couple of years. This is because the sun is nearing its peak sunspot cycle. Just like almost everything else in our galaxy, the sun goes through different types of cycles. One of those is a very predictable sunspot cycle. Every eight or so years, the sun goes from high sunspot activity to almost no sunspot activity at all. With more sunspots, you get more particles thrown toward the Earth on average, and therefore often have more robust and brilliant aurora.

The sunspot activity is on the upswing and is likely to peak sometime in late 2024 or 2025. But this peak is already stronger than the last one, which means we have more sunspots than we've seen in almost 20 years. This will quite likely give us the best opportunity to see the Northern Lights across much of the U.S. in the last couple of decades. That doesn't mean it will happen, but the chances are much higher than they have been in a while.

Tips for seeing the Northern Lights

So here are some quick facts to keep in mind over the next few days, weeks, and months if and when you attempt to see the Northern Lights:

- Always get as far away as possible from light pollution and large cities. While a strong CME would make it possible for the Aurora to be visible in a city, this is seldom the case, especially the farther south your location is in the United States.

- You will NOT see the aurora if there are clouds. Remember that the aurora lives dozens of miles above our weather, so any clouds will obstruct your view.

- Try to get an unobstructed view of the northern horizon. A strong CME could make the aurora appear more overhead. But it is far more likely that many of us will only be able to see them lower than 30 degrees above the northern horizon.

- The aurora is extremely variable and changes quickly over very short periods of time. Even some of the strongest CME's can have very short lifespans where the aurora are visible. You may sit and watch the horizon for hours only to get a sporadic 5-minute show of brilliant colors. In most cases, there is just no way to know for sure how the event will unfold for every location.

- Be extremely skeptical of any aurora forecast more than 48 hours away. When a CME is discharged from the sun, it will take roughly 36 to 60 hours to reach Earth. There is no way to predict when a CME will occur, so aurora forecasts are entirely reactionary and not predictive. If you see a story/post/comment expecting the Northern Lights to be visible more than 2 days away, I would not consider that credible information.

- In the Lower 48 states, the aurora will not look as good with your eyes as what many professional cameras can capture and the corresponding images that are then posted online. Cameras can be far more sensitive to the variation in light and color with long exposures compared to the human eye. Only when the aurora are high in the sky will they appear close to what is seen from a long exposure photograph.

- The strongest CME's can actually cause significant issues for humans. If they are strong enough, transformers at power stations can be overloaded, damaging the power grid, and creating large blackouts that would have the potential to last for weeks, depending on how badly damaged the power grid is. This type of event is VERY rare, so don't lose sleep over it. But it is possible and slightly more likely during peak sunspot years. The more likely scenario for stronger waves is that radios become inoperable thanks to static, and satellites temporarily lose the ability to communicate with transmitters here at the surface. So things like GPS, cell phones, and satellite tv would stop working for a relatively short period of time as the wave moves through.

- While the meteorologists at FOX 9 will try to keep you updated on more "legitimate" chances to see the Northern Lights, we are not experts on the subject. You can get a forecast from the experts at the Space Weather Prediction Center here or with an off-branch of NOAA at spaceweather.com

Thursday's forecast: Sunny, highs in the 80s

Plenty of sun for the next couple day with some isolated storms possible.