Wildfires: Simultaneously our friend and foe

Using fire to improve landscape in Minnesota

Prescribed burns, as they're often called, have become commonplace across the country, including right here in Minnesota. In fact, the city of Burnsville is using fire to transform its heavily forested city parks back into the oak savannas they once were hundreds of years ago. With several hundred acres of parks, they will be transformed over the course of many years. But it's already underway in Terrace Oaks Park with roughly one-third of the 220-acre park restored.

BURNSVILLE, Minn. (FOX 9) - The interest in information about wildfires (or forest fires) has soared this year thanks mostly to the wildfire season exploding in Canada and the associated smoke that's blanketed parts of the U.S. several times since May. These fires are both naturally occurring and beneficial — and, in many cases, necessary evolution of forests and grasslands alike. But it's far more complex than that with humans directly affecting our landscape in both good and not-so-good ways.

History of fire in the US

There is a long and complex past with humans and fire, especially in the U.S. Several hundred years ago, Native Americans used fire as a hunting aid, to clear brush and debris, and to help kickstart plant production with naturally growing trees and bushes like blueberries. When Europeans arrived and spread across the continent, they used fire to clear millions of acres of land for crops and settlement. That's essentially what shaped the croplands we see today in what is now the Great Plains and Midwest.

The amount of burning that occurred in a lot of the 1800s would be considered absolutely staggering today, with hundreds of millions of acres of forests, estuaries, and great savannas set ablaze. But by this point, human-sparked fires were both intentional and unintentional. Intentional fires were still set to make room for settlements, help clear space for crops, as well as being used as a tool for large-scale projects that we use backhoes, tractors, and cranes for today. But there was now a drastic increase in careless fires. Many erupted from travelers letting their warming bonfires spread before extinguishing them. The railroads were also prevalent by this point, going from coast to coast. But early locomotives would create large sparks that started countless wildfires.

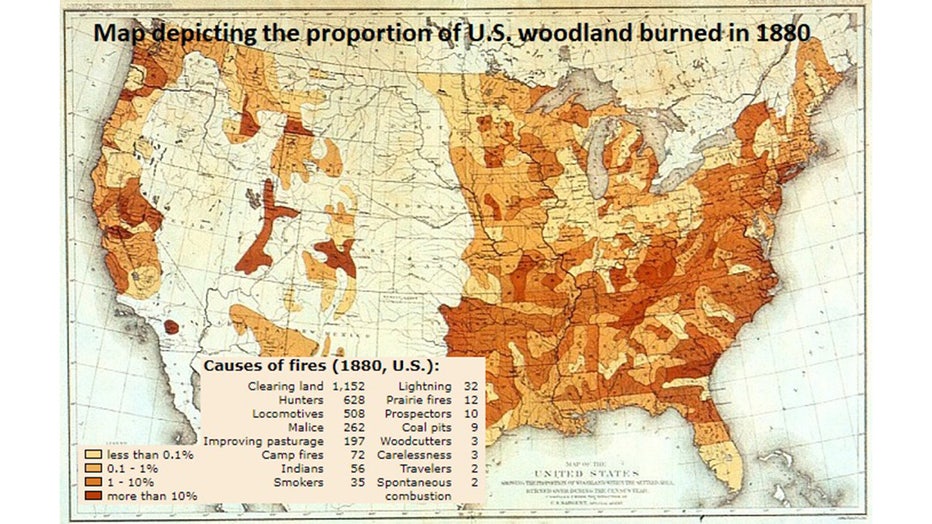

This is a map from the National Humanities Center that shows the sheer amount of land that was burned in just one year in the late 1800s:

Fires in 1880.

By this point, the amount of burning was getting out of control. And with the U.S. government and subsequent population continuing to grow, so was the concern that this would create issues in the future. So the Forest Reserve Act was enacted in 1891 to help preserve some of our forests for future generations. Then Theodore Roosevelt helped Congress create the U.S. Forest Service in 1905, which would be dedicated to the preservation and upkeep of forest areas across the country. Prevention became the standard for the U.S. for decades to follow for two big reasons:

- It was thought that fire was entirely bad, destroying all that it touched

- Logging was one of the largest industries in the U.S. and many were concerned that fires would destroy a lot of the "product" that we used for almost everything

To drop the number of acres burned, starting a fire either intentionally or from recklessness, became a felony with massive fines and jail time. Also, thousands of men were hired to help fight these wildfires and squelch them as quickly as possible. This was incredibly effective with acreage burned dropping drastically in the years that followed. This eventually led the way to an advertising campaign around the creation of Smokey the Bear in 1944.

We now know fire can be a good thing

But what we didn't know was that fire had long been a naturally occurring element in the landscape. If humans weren't present, lightning would likely still cause thousands of fires every year with tens of millions of acres going up in flames. These fires would be prevalent enough in most cases that most areas would see some sort of fire every so often, maybe once a decade or so on average. Because of this, grasslands and forests alike would be constantly thinned. This would allow the hardy plants to survive and the not-so-hardy or already dead ones to be burned, adding nutrients back into the soil. It would also keep sunlight abundant to restimulate growth as soon as the soil recovered from the fire, which ranged from just a few days to the start of the next growing season at worst.

So now in 2023, with more than 100 years of fire suppression, there are many wooded areas that haven't experienced a fire in the better part of that time. That has led to a substantial overgrowth in many wooded areas. Invasive species that would otherwise be burned out have expanded exponentially (like buckthorn for example), forcing native plants to drastically recede, or even go extinct in some cases. With so many plants succumbing to overgrowth or just their natural end-of-life cycle, there is an incredible amount of fuel that can burn if a fire is sparked. This is what leads to the destructive fires we know today. They burn incredibly hot (more than 2,000 degrees in some cases), which doesn't allow the natural fire-resistant plants, or anything else for that matter, to survive. So, the landscape becomes a wasteland when the fire has been extinguished. It then takes decades for the area to return to what it once was.

Without consistent fire, the cycle will just repeat itself somewhere in the future.

Returning the landscape to the sustainable state it once was

Now that we know this, we can start taking action. Prescribed burns, as they're often called, have become commonplace across the country, including right here in Minnesota. In fact, the city of Burnsville is using fire to transform its heavily forested city parks back into the oak savannas they once were hundreds of years ago. With several hundred acres of parks, they will be transformed over the course of many years. But it's already underway in Terrace Oaks Park with roughly one-third of the 220-acre park restored. According to the Natural Resources Specialist Caleb Ashling, it's a three-step process.

"So, our first step is doing some tree thinning, removing invasive woody species, and opening the area up. And then after that we bring in native plant seed grasses and wildflowers so we can really restore that understory plant community that's gonna provide that low-intensity fuel to use controlled burns as a management tool. And then lastly, once that understory is developed, we can use regularly controlled burns for our long-term sustainable management plan," Ashling said.

It's very plain to see how our once abundant oak savannas are all but gone. Check out the difference in these aerial photos from the Burnsville area in 1937 and then in 2011:

The restoration years of the park have been superimposed on the map to give you an idea of where they are. In 1937, trees were very much present, but fairly sparse overall. These oak savannas encompassed much of the Interstate 94 corridor before fire suppression and population consumed the landscape. They were the transition zone between the grassy areas of southern Minnesota and the deciduous forest areas of northeast Minnesota and northern Wisconsin.

So, here's what the park looks like before and after the transformation back to the natural oak savanna:

The area goes from an overgrown mess to a very inviting landscape suitable for animals, pollinators, and humans alike. And it turns out that fire is really the icing on the cake to keep our natural habitats healthy. More often slow burning fire means more pollinators to help the area flourish with life, according to pollinator expert Heather Holm.

"A fire helps regenerate the perennial and grass species that grow in more open habitats. So that creates higher plant diversity that pollinators rely on. Very few deciduous trees that grow here in Minnesota rely on insect pollination. So most of the pollinator habitat is made up of these flowering perennial plants. So, when we have a closed canopy forest, we have very few perennial plant species that can grow in that system," Holm said. "That's why light is so important and the reintroduction of fire helps maintain very diverse systems with more flowering plants."

The funding for the Terrace Oaks Park project is mostly from the Conservation Partner Legacy program of the Minnesota DNR. It helps fund many other projects that are similar across the state. For more information on how all of this works, as well as a workshop you can attend that covers all of this, you can visit the city of Burnsville's website.