Why Plymouth PD and local police are increasingly turning to negotiator teams

(FOX 9) - In early March, a pair of police standoffs occurred in the metro area on the same Friday, one in Hopkins and another in St. Anthony. They garnered little media attention beyond a passing mention in local TV newscasts.

On Friday, March 5 at 8:36 p.m., Hopkins police responding to a domestic call encountered a man in an apartment on the 700 block of Cambridge Street who refused to come out. When officers came to the door, he threatened them and then shot through it, police said. After seven hours of negotiations with police, the suspect came out with his hands up around 4 a.m. Saturday. No one was hurt.

Earlier in the day on Friday, another police standoff happened in St. Anthony. At about 3:45 p.m., police responded to a home where a 16-year-old boy had allegedly been involved in a "physical domestic" with his mother, according to the police report.

Police learned that the boy was potentially on the autism spectrum and suffered from bipolar disorder as well as anxiety, but had stopped taking several of his medications, the report says.

The teenager locked himself in his room. Through a crack in the damaged bedroom door, an officer noticed the boy was holding a three-to-four-foot-long sword. It was still sheathed, but the boy told officers that if they entered the room, they would never leave, the report says.

A negotiator managed to talk to the teenager through the bedroom window and convinced him to leave the room peacefully. The talks continued in the kitchen. There, after lengthy conversations, the teenager eventually agreed to be taken to the hospital for evaluation, as his mother had requested, according to the report. Again, no one was hurt.

But beyond the bare facts of the two incidents, there was a remarkable and unnoticed achievement.

An officer in the Plymouth Police Department — a woman who works undercover and therefore can't be named — had been the lead negotiator in both incidents. She had used her training in active listening and other emotionally intelligent and psychologically informed negotiation techniques to resolve two scenarios that, if police had approached them differently, could have ended in violence and put both civilians’ and officers’ lives in danger.

"The training involved and the level of expertise and professionalism is hands down the reason that these situations are resolved successfully and without injury to all involved," Hopkins Police Chief Brent Johnson said in an interview with Fox 9 after the standoff. "It really is so crucial that we have trained negotiators who are able to deescalate situations that are tense and rapidly unfolding."

‘Looking more and more at negotiations’

The achievement of the Plymouth police negotiator was not an isolated, one-off incident, but instead reflects a broader shift within local police departments, including the Plymouth PD, to prioritize and grow their police negotiator teams. That trend accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic when departments faced a growing number of mental health calls, many involving armed suspects

Plymouth PD started a mental health unit with an embedded social worker in 2019. Between 2020 and 2021, calls referred to the mental health unit jumped by 27 percent, to 840 incidents.

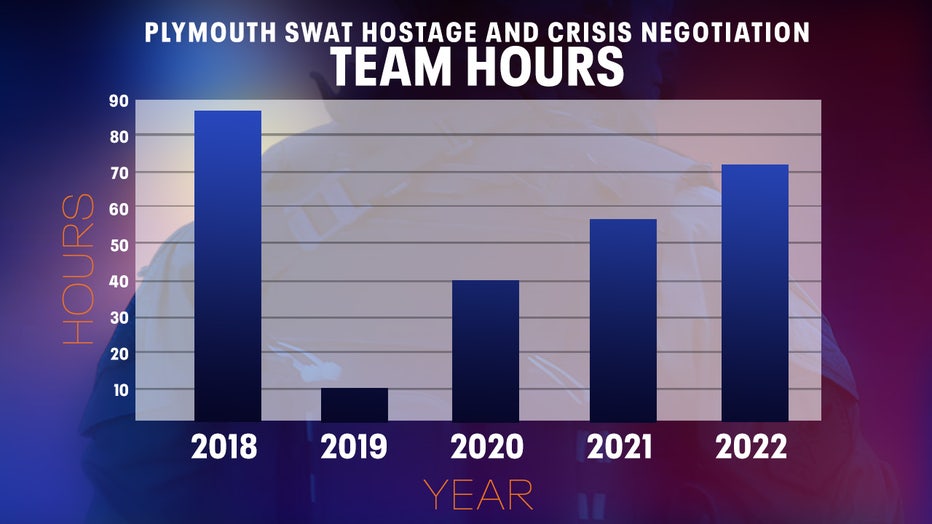

Meanwhile, the total hours logged by the Plymouth SWAT Hostage and Crisis Negotiation team steadily climbed over the next three-year period, according to figures provided by the department.

In 2018, the team logged 87 hours over three major incidents, or "call outs," which the department defines as dangerous events that require a full team. This dropped to nine hours in 2019, split over one major incident and five minor ones, or "non call outs," – incidents, that while still dangerous, don't require the full team and can be handled by one or two negotiators.

Then the numbers began to rise. In 2020, there were four team call outs and two non-call outs, for a total of 39 hours. In 2021, there was only one full team call out, but five non-call outs, resulting in 55 total hours.

Only four months into the year in 2022, the team has already surpassed last year’s total and has logged 70 hours, with two team call outs and five non-call outs.

These include incidents in which Plymouth PD negotiators were called to help other nearby departments, like the case in Hopkins.

The negotiation team has grown to meet the demand, doubling from four to eight members between 2017 and 2020, according to department figures. Plymouth partnered with Maple Grove to increase their capacity further, creating a combined team of 16 officers potentially available as well as two advisors — a psychiatrist and a technical advisor.

"As the needs of our community continue to change, we have seen that having a team of highly skilled crisis negotiators is critical to making sure that we are finding the safest, most peaceful solutions to helping people in crisis," Plymouth Police Chief Erik Fadden explained.

Sergeant Scott Whiteford, the head of the negotiator team at Plymouth, said the increase in the number of calls involving armed suspects was an important factor.

"The larger amounts of calls, where we have weapons involved or somebody is barricaded, whether it's a mental health issue or criminal issue, was increasing as well. So looking into the future, we decided that we need to put more emphasis on the role of appointing more negotiators," he said.

FBI Agent Christopher Langert is an FBI negotiator who also oversees the training of local police negotiators in Minnesota. He says he’s seen departments across the state take the same path as Plymouth PD.

"I have seen, over the last decade, that more and more teams are seeing the necessity of having specially trained crisis negotiators as part of their deployment or as part of their response. And I have seen that the teams that already knew that are becoming more robust as well," he said.

And the move toward negotiation may also reflect a cultural change happening within policing that has seen traditional "command and control" tactics de-emphasized, at least in certain scenarios, in favor of approaches that incorporate de-escalation and dialogue.

Langert has seen that shift occur at the federal level.

"We are looking more and more at negotiations in our approaches to things like search warrants, arrest warrants… more frequently than your traditional "No announce" search warrant, which we've gotten away from for years now," he said.

For the state's largest police force, the Minneapolis Police Department, the trend is more nuanced.

According to Public Information Officer Garrett Parten, MPD recently added two officers to their Crisis Negotiations Team, but that was to fill open positions. The team has 12 officers total. Like Plymouth PD, they also work with a mental health professional and a social worker.

Parten says that since 2020, MPD's negotiator team has seen a "slight increase" in deployments. However, he notes that over the last few years, all sworn officers have been trained in Critical Incident Training (CIT), a form of de-escalation training specially geared toward dealing with subjects in a mental health crisis. This, he says, has meant the department has had less of a need to turn to the negotiator team than it did previously.

"The initial response by trained patrol officers has been effective in dealing with persons in crisis," Parten says.

"A team sport"

In Whiteford’s view, depictions of police negotiators in TV and movies have led to some common misperceptions, namely that it’s about "talking and quick results."

"Really negotiation, it’s a very long process that requires more listening — listening to make sure that we're catching a person's tone, the inflection of their voice... it takes a huge team. It's not just one person talking," he said.

Langert describes it as a "team sport." Beyond the lead negotiator, or the person doing the talking with the subject, other designated roles include:

Team leader: Coordinates information coming out of the Negotiations Operations Center, or NOC, to other parties, including command, SWAT and the media or public information officer.

Coach: Responsible for providing support to the negotiator and providing an outside perspective on the negotiations. "You’re not in the hot seat, so you're much more likely to hear things when you're not under the stress of being the primary. You might hear certain emotions, and write a note to your primary saying something like "This guy sounds really betrayed," Langert says.

Intel: Team member who researches the subject and their social connections, like family, friends, clergy and work colleagues, to better understand their perspective and who might be able to reach them. "Who could speak to this person? Who could give us good information about some of the things that are important in their life?" Langert says.

Recorder/Scribe: Organizes and displays key information for the lead negotiator on boards or monitors, so the negotiator can quickly reference it while in talks.

Tactical liaison: Listens to the negotiators for tactical details that could be important for SWAT if an armed intervention is necessary -- like what weapons the subject has, or the location and condition of any hostages.

A complex negotiation often involves officers across different departments. There were 10 officers on the negotiator team for the seven-hour standoff in Hopkins: six from Plymouth, two from Minnetonka, one from Eden Prairie and one from St. Louis Park, along with the psychiatrist who works as an advisor with the Plymouth PD.

Hope for the next day

While all the roles in the negotiator team are important, intelligence gatherers can be particularly critical in cases where the negotiator needs the help of another person to get through to the subject.

Whiteford recalled a recent case when he was part of a team that was negotiating with a man who was sitting in a bathtub with a gun to his chest, threatening to pull the trigger.

"We had an individual who could not get past the fact that his future might be ruined because of what he was doing. He couldn't get past today, the moment. Didn't have that hope of the future," Whiteford said.

A member of the negotiation team reached out to the man’s family and found someone the man trusted to record a message. The negotiator then played the message out to the subject.

"That was enough to calm the person's emotion down, gain that trust that we're trying to let them know that there's hope down the road, we just have to get past today," Whiteford said.

The man surrendered to SWAT. Whiteford stressed that in his view, ultimately it’s the subject, not the negotiators, who decides how a call turns out.

"Whether it turns out good or bad, they're the ones that make that decision. So as a negotiator, we're trying to influence their decision-making to come out peacefully, like in the Hopkins incident at the very end of it. The person ended up coming out, agreed to be arrested. That was a decision that he ended up making," Whiteford said.