Spring allergies have been brutal — and they're getting worse

A woman blows her nose behind birch blossoms. Photo: Karl-Josef Hildenbrand/dpa (Photo by Karl-Josef Hildenbrand/picture alliance via Getty Images)

MINNEAPOLIS (FOX 9) - Our delayed spring warmth may be the reason why many are suffering from spring allergies right now.

According to the Allergy and Asthma Association of America, 81 million Americans have been diagnosed with some form of seasonal allergies. Considering many of us don't see a doctor on a regular basis, or can just get by with over-the-counter medication, the realistic number of folks that have symptoms from nature is likely a lot higher. Thanks to the colder temperatures lasting a bit longer this year, essentially into early May, vegetation has been dormant and prepping for the spring green up. Now that we have turned the corner, that delay is leading to our vegetation exploding to life all at the same time, which then leads to an explosion of pollen into the atmosphere as well. When levels get high enough, even those that don't typically have allergy issues can see some minor symptoms.

Now, I'm not an expert on plants or pollen, but the weather certainly plays a role — and it's seemingly getting worse.

If you are someone who's only started getting allergy symptoms in the last few years, I'm not surprised. While anyone can become increasingly sensitive to pollen at any time, the amount of pollen that you're exposed to can also lead to an oversensitivity. It's this reaction that gives us the symptoms that we get so used to feeling or at least hearing about. But there's an alarming trend occurring that has many scientists not just scratching their eyes, but scratching their heads.

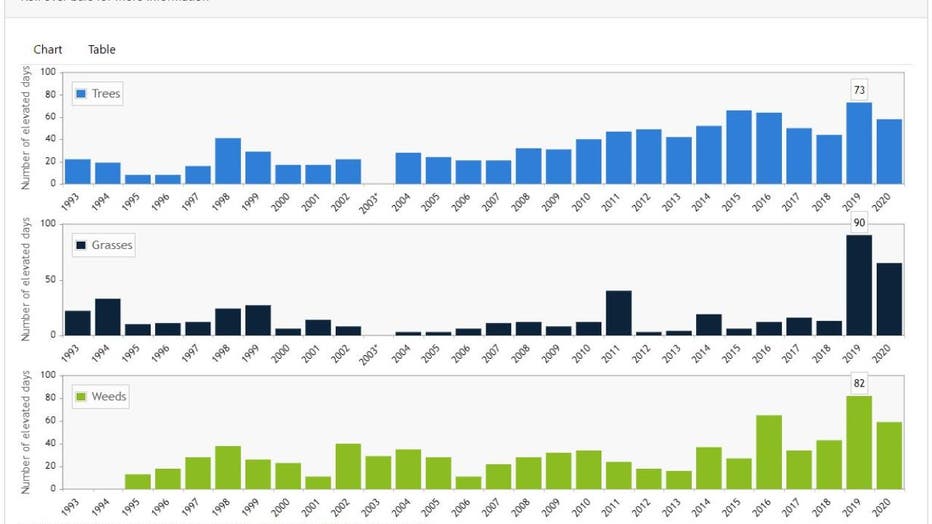

Number of elevated pollen days in Minneapolis. (Clinical Research Institute, Inc.)

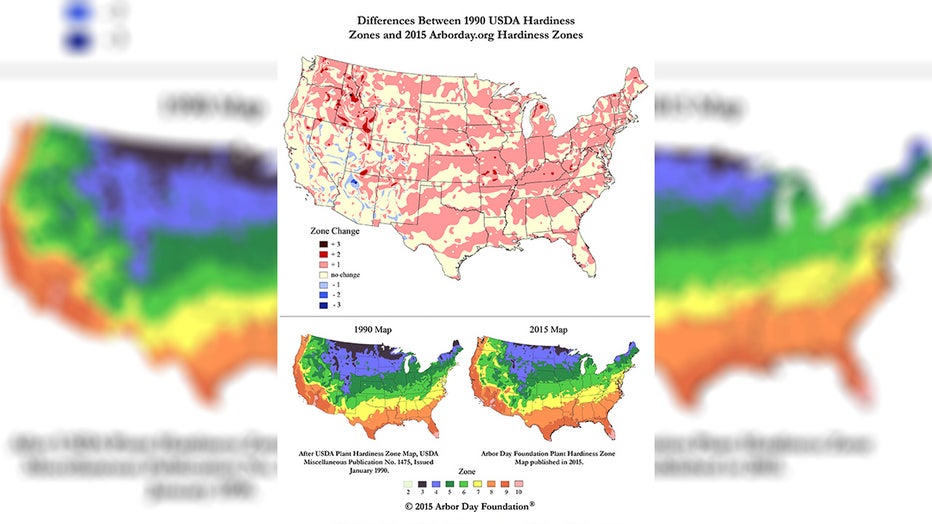

According to research from the Minnesota Department of Health, the amount of pollen in the atmosphere, including "high pollen days" has been increasing for decades. While the reason for this isn't really known, it's alarming because the number of trees on Earth is at its lowest point in human history, according to a 2015 study from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Crop and grass coverage is also not thought to be at their highest levels either. So why the increase? Climate change is widely believed to be the driver here, with longer growing seasons in general. But it's likely a lot more complex than that. My hypothesis is a combo of longer growing seasons and more CO2 in the atmosphere, which is what plants "eat". This gives them more "food" and therefore allows them to grow faster and fuller, and therefore produce more pollen. I'm sure there are several unknown variables as well. These changes have also led to a noticeable difference in hardiness zone classifications for vegetation across the country over the last 25 years or so.

Hardiness zones in the United States.

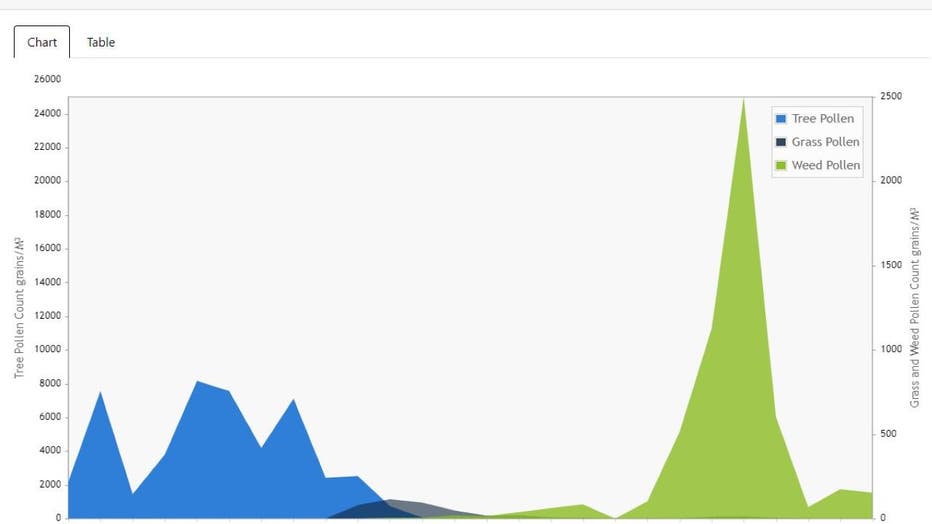

There are three main sources of pollen in the atmosphere: trees, grass and weeds. Each has a different "season" that they release pollen, that can lead to a flourish and fade effect for allergies through the warm season. That's the main reason why some weeks are worse than others from April through October. Now, because trees are the largest of these objects, they typically produce and release the most pollen and lead to the worst symptoms.

Weekly pollen counts by type in Minneapolis in 2020. (Clinical Research Institute)

In the image above, the pollen count for trees is on the left, grass and weed pollen is on the right, and the passage of time is on the bottom of this graph. The three types of vegetation all release pollen at different points of the year. In the spring, it's all about the trees as they emit an astronomical level of pollen. Trees emit roughly four to eight times the amount of pollen that comes from grasses and weeds. This is the big reason why so many of us suffer from spring allergies. Once tree pollen wanes, then ground temps are warm enough for grass to emit fairly low but persistent pollen through much of the summer. Then in late summer and real early fall, ground temps peak pushing ragweed to pollinate to reproduce for the next year. Ragweed season is quite short, but is often quite intense with a late season burst of pollen comparable to the spring, but usually lasts just two or three weeks right around the State Fair. That's the reason I'm usually suffering from itchy eyes and LOTS of sneezing while I'm outside enjoying the Great Minnesota Get-Together.

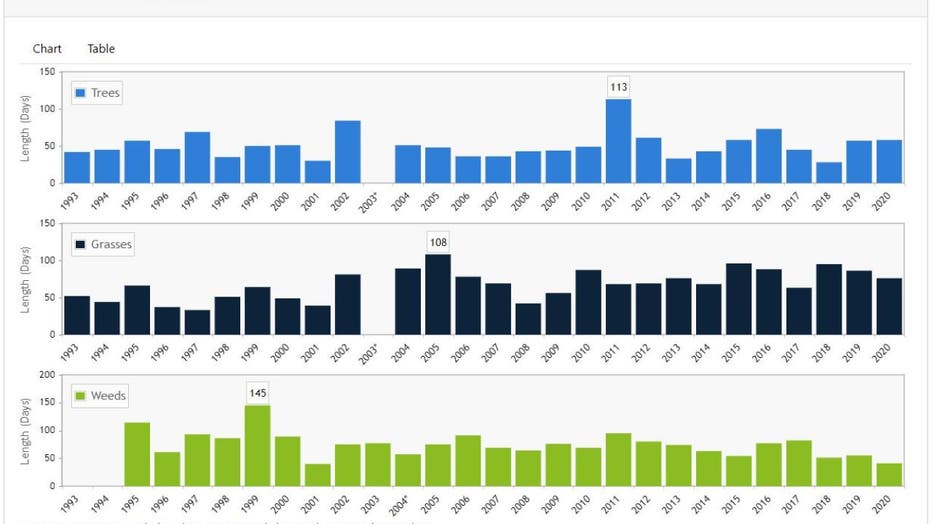

Length of the pollen season by year in Minneapolis. (Clinical Research Institute)

Once we get past the Minnesota State Fair, the pollen count usually plummets for the rest of the year as we head into the cold season. But with our fall trending much warmer over the last 20 years, pollen levels have often been holding relatively high all the way into early October, before drastically falling after that. The conclusion? You may want to get used to having a longer allergy season because if this trend continues, it's only going to get worse.